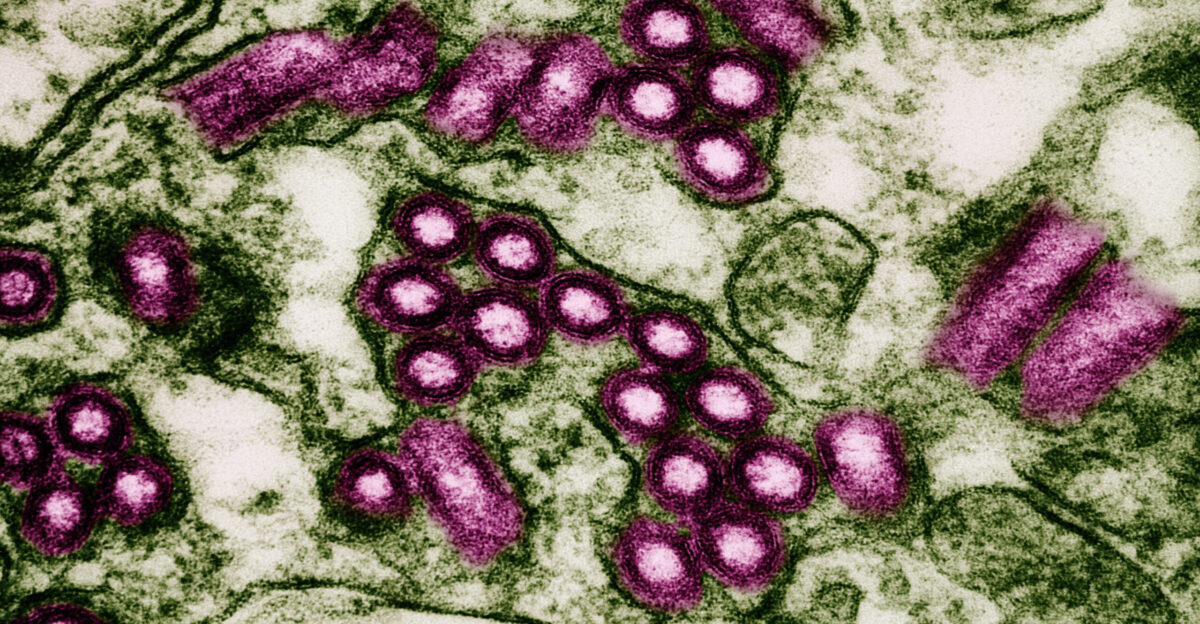

With 15 active clusters spread across several U.S. states, the 2025 rabies outbreak is said to be the largest in recent memory. Nearly all untreated cases of the viral zoonotic disease rabies result in fatal encephalomyelitis. 99% of human cases worldwide are caused by domestic dogs, and it is primarily spread by the bites of infected animals. Wildlife like bats, raccoons, foxes, and skunks are among the rabies reservoirs in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is monitoring 15 probable outbreak clusters from New York to Oregon and has recorded six human deaths in the last year, the most in recent memory. Increased wildlife infections amid habitat changes and improved surveillance are linked to the rise.

Rabies Outbreak Trends Throughout History

Rabies outbreaks, particularly in dog populations, have historically fluctuated with notable peaks worldwide. For example, rabies cases in South Africa increased during the 1990s and early 2000s before declining somewhat. The main cause of outbreaks has been domestic animals, especially dogs; wildlife cases have remained largely unchanged but are probably underreported.

Periodic spikes have been caused by reactive rather than preventive rabies control measures. Since the late 20th century, outbreaks have been occurring frequently in various geographic clusters in the United States due to wildlife reservoirs, especially raccoons and bats. Increased human-wildlife interactions, environmental disturbances, and deficiencies in preventive veterinary care are all factors contributing to the current state of affairs.

Interactions between Domestic Animals and Wildlife as Drivers

An important but underappreciated factor in the spread of rabies is wildlife. Although the majority of human cases of rabies are caused by dogs, transmission cycles can be maintained or new outbreaks can be brought about by foxes, raccoons, skunks, and bats. Although domestic dogs can spread the virus to humans and livestock, they also act as conduits for the spread of rabies between human populations and wildlife.

Containment is made more difficult by cross-border animal interactions and movements; for instance, black-backed jackals in South Africa have been linked to the borders of Lesotho. Even in places where domestic dog vaccination programs are in place, the viral reservoir in wild canids poses ongoing risks, indicating the need for comprehensive, One Health strategies that integrate the management of domestic and wildlife animals.

Present Rabies Outbreak Clusters in the United States

The 15 distinct rabies clusters that the CDC keeps an eye on are spread throughout the states of New York, California, Oregon, Maine, North Carolina, Indiana, and Vermont. Notable hotspots include rabid fox outbreaks in western states and Nassau County, New York, where there have recently been health alerts due to rabid animals.

As urban sprawl encroaches on natural habitats, raccoon and bat populations, primary reservoirs in their respective regions, become more and more infected. Human risk has increased as a result of increased animal bites and wildlife with positive rabies tests. This year’s heightened season, as evidenced by an increase in rabid animal calls and reports, suggests significant outbreaks rather than isolated incidents, according to surveillance data.

Public Health Issues During the Resurgence of Rabies

Uneven surveillance systems, dispersed funding, and political disengagement continue to be obstacles to rabies control. The veterinary, public health, and agricultural sectors frequently lack continuity and integration in dog vaccination, which is crucial for rabies control. 8.6 billion is spent on treatment and lost livelihoods worldwide each year as a result of rabies.

Risks are increased in many areas, such as parts of South Africa and the United States, by a lack of public awareness and insufficient access to post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). Potentially contributing to the current spike were setbacks in routine vaccinations and public health outreach brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Gaps in the fight against this avoidable disease are caused by inadequate data systems and uneven vaccine availability.

The Psychological and Emotional Cost of Rabies

Beyond just causing physical sickness, rabies causes severe psychological suffering for victims, their families, and entire communities. Trauma, anxiety, and fear are prevalent, especially because symptoms are almost always fatal. Exposure survivors frequently experience persistent mental health issues, such as anxiety disorders, depression, and panic attacks.

Fear of animals and widespread mistrust of healthcare systems are developed in communities that experience human losses. The euthanasia of unvaccinated pets and the annoyance of avoidable deaths are two more emotional burdens that veterinarians must deal with. These unseen emotional scars emphasize how important psychological assistance is to all-encompassing rabies control plans.

South Africa’s Parallel Rabies Epidemic

Hotspots in the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, and Limpopo regions of South Africa serve as prime examples of the dire repercussions of domestic dog rabies outbreaks. Alongside an increase in human cases, more than 400 canine cases have been reported in Nelson Mandela Bay alone since 2021. Nearly 20 laboratory-confirmed human cases were reported by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in 2021, a notable increase associated with canine outbreaks.

This scenario emphasizes the necessity of strong vaccination campaigns and public education by illuminating the direct correlation between human rabies incidence and domestic dog epidemics. The situation in South Africa is similar to those in the United States, where unchecked animal reservoirs contribute to broader transmission.

The Effects of Outbreak Expansion on the Second and Third Order

Widespread rabies outbreaks exacerbate downstream socioeconomic and ecological effects in addition to the immediate health risks. Healthcare systems are under stress from human deaths, disruption of livelihoods due to animal phobias, and medical treatment costs. Loss of working animals and control program costs are examples of economic burdens.

Increased stray animal or wildlife culling upsets ecosystems and, ironically, can spread rabies if displaced animal populations migrate or adapt. Social cohesiveness and confidence in authorities are negatively impacted psychologically by community trauma. Outbreaks may also lead to more stringent animal control regulations, which would affect the rights of pet owners and rural communities that depend on dogs for livestock protection or security.

Could Perceptions Be Skewed by Increased Surveillance?

Public health officials are alarmed by the current high number of clusters, but another interpretation contends that perceptions of increased outbreak severity may be influenced in part by better reporting and surveillance. Better diagnostics, increased public awareness, and improved testing may increase the number of cases found without increasing the true prevalence of the disease by the same amount.

Debates about the distribution of resources and division over public health priorities may result from this. However, the existence of multiple concurrent clusters continues to be a concern for control strategies and public safety, even if the numbers show improved detection.

Rabies in Unusual Wildlife Hosts: A Case Study

In South Africa, recent reports have confirmed rabies in unusual hosts like seals. This extraordinary event demonstrates how the virus can adapt to new ecological niches and transcend species boundaries. Seals are not common reservoirs, but these spillovers complicate outbreaks and put current control strategies to the test.

It emphasizes how important it is to monitor wildlife widely outside of common reservoirs in order to foresee new threats and safeguard a variety of ecosystems and human populations.

Insights from Past Epidemics

Important lessons about prevention and control can be learned from previous rabies outbreaks. The 2006 rabies outbreak in South Africa, for example, demonstrated how vaccination errors and underestimated wildlife reservoirs frequently cause peaks.

The significance of oral rabies vaccination for both domestic and wildlife animals is reinforced by similar past outbreaks in the United States associated with raccoon rabies. Improved risk assessment, targeted vaccination, and early intervention are made possible by an understanding of the epidemiological patterns of these earlier waves.

A Psychological Framework for Handling the Effects of Rabies

Community education to lessen stigma and fear, trauma-informed care for bite victims and their families, and mental health support for frontline workers like veterinarians should all be incorporated into a comprehensive psychological framework to address rabies.

Customized communication tactics can reduce false information while enabling communities to practice prevention and post-exposure behaviors. In addition to medical interventions, programs that acknowledge the psychological and social effects of outbreaks provide long-term resilience building in areas that are at risk.

Effects on the Agriculture and Veterinary Industries

Agriculture and veterinary services are severely impacted by rabies outbreaks. Increased workloads for animal culling, vaccinations, and diagnostics frequently cause veterinarians emotional distress. Food security and rural economies are negatively impacted by livestock losses due to rabies infections.

To stop outbreaks at their source and stop them from spreading to people, comprehensive animal health programs that connect vaccination, surveillance, and farmer education are desperately needed.

Socioeconomic Inequality and Rabies

Economically disadvantaged groups are disproportionately affected by rabies because they have less access to healthcare and vaccines, which delays prompt intervention. In addition to living near wildlife habitats and frequently lacking the infrastructure necessary for animal control, rural and underdeveloped communities are more likely to be exposed to stray or wild animals.

Because it takes lives, livelihoods, and financial resources, this disease exacerbates cycles of poverty. To eliminate this long-standing public health disparity, equity in control programs must be given top priority in strategic engagement and funding.

Technological Advancements in Rabies Monitoring and Management

Outbreak monitoring is improved by cutting-edge technologies such as geographic information system (GIS) mapping, drone surveillance for wildlife reservoirs, and enhanced laboratory diagnostics. Real-time data sharing between public health and veterinary authorities is made possible by digital platforms, which speed up response times.

Oral vaccines for wildlife and longer-lasting dog vaccinations are examples of vaccine delivery innovations that can increase coverage and lower logistical obstacles. In the face of growing clusters, these technologies offer chances to maximize control.

Urbanization and Environmental Change’s Role

The epidemiology of rabies is impacted by rapid urban sprawl because it increases human-wildlife contact.

Because of habitat fragmentation, wildlife are forced closer to cities, which makes it easier for viruses to spread. Furthermore, alterations in land use can modify animal behavior and population dynamics, which can impact the patterns of rabies transmission. To reduce the likelihood of outbreaks, zoonotic disease risk assessments should be incorporated into environmental conservation and urban planning initiatives.

Possible Worldwide Dispersal and Cross-Border Hazards

Human and animal mobility increases the possibility of rabies spreading across international borders. Previously rabies-free areas may become infected with rabies due to wildlife migration and the illicit animal trade. This risk is exemplified by the introduction of rabies to Australian dingos through nearby regions.

To stop the virus from spreading geographically, border surveillance, international cooperation, and vaccination policy harmonization must all be strengthened.

A Public Relations Approach to Handling Fear of an Outbreak

During rabies outbreaks, accurate, timely, and transparent communication is crucial to controlling public anxiety and avoiding false information. Authorities must give clear instructions on prevention, exposure response, and available medical resources while striking a balance between warning the public and preventing panic.

Cooperation with containment efforts and reporting are encouraged when the community is engaged through reliable local channels. Oversharing evidence-based scientific facts increases resistance to stigma and rumors.

The Need for Coordinated Action Now

The 2025 rabies outbreak necessitates immediate, coordinated multi-sectoral action due to its highest cluster spread in years. The tide can be turned by combining strong vaccination campaigns, scientific surveillance, psychological support, and socioeconomic equity considerations.

Ignoring the many effects, such as the psychological, ecological, and economic ones, could make this public health emergency worse. The only viable way to stop more deaths and loss of livelihoods from this long-standing but persistent viral threat is to adopt a global One Health approach that integrates human, animal, and environmental health.