Scientists once thought that human evolution was straightforward: apes gradually evolved into humans. A new discovery in Ethiopia changes that.

Researchers have found fossilized teeth that prove Homo—our genus—existed millions of years earlier than previously believed. It walked alongside another human-like species for hundreds of thousands of years. Early humans shared their world with cousins, not alone.

Human evolution wasn’t inevitable progress; it was a sprawling family tree with many branches, some thriving and some vanishing.

Timeline Under Pressure

For decades, scientists believed Homo emerged around 2.3 to 2.4 million years ago, based on Homo habilis fossils.

That timeline filled textbooks and museum exhibits. Yet it left gaps. How did the transition happen? What came before?

These questions puzzled researchers in Ethiopia’s Afar Region, which holds Earth’s richest fossil records. They were about to find answers nobody expected.

The Afar’s Hidden Archive

Ethiopia’s Afar Triangle is ground zero for human origin discoveries. Since 1974, major finds have emerged, including Lucy, a 3.2-million-year-old Australopithecus, which shows that our ancestors walked upright before developing large brains.

The Ledi-Geraru Research Project, launched in 2002 by Arizona State University, systematically excavated this region. Volcanic ash layers allowed precise dating using argon-argon methods. Even experienced scientists were unprepared for what lay beneath the surface.

A Mandible Changes Everything

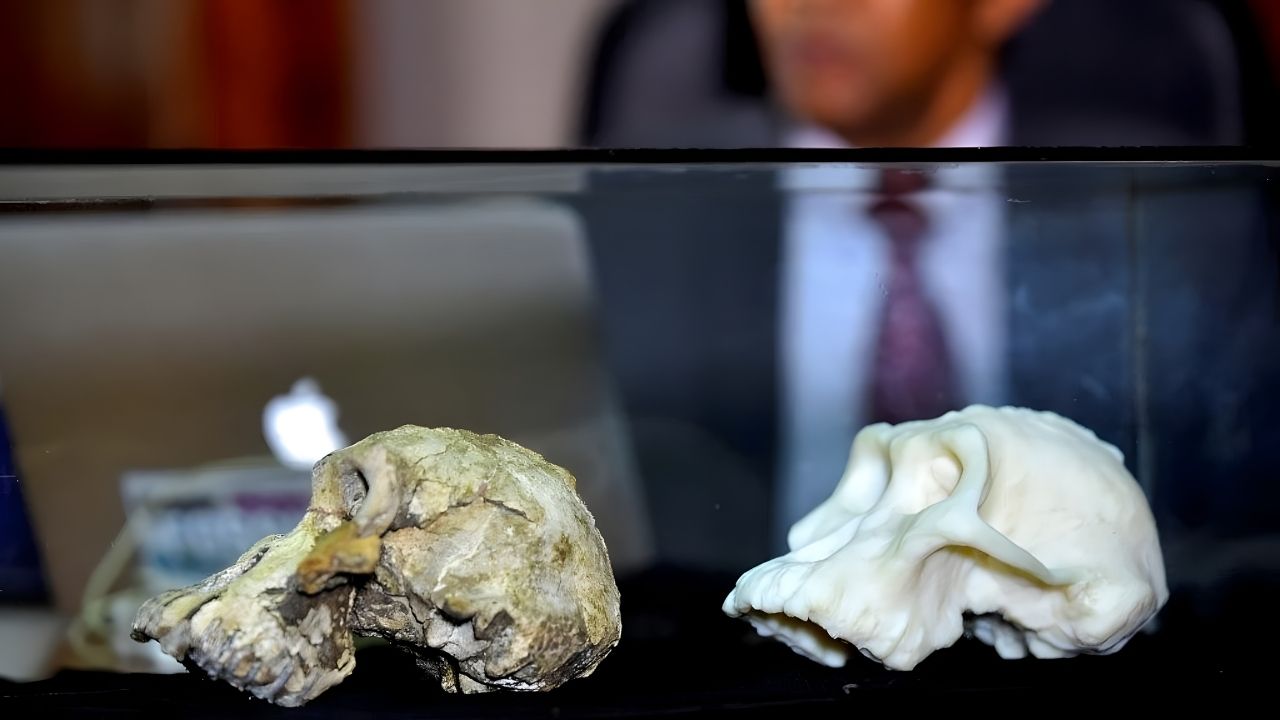

In 2013, excavators discovered LD 350-1—a jaw with teeth dated between 2.75 and 2.8 million years ago—at Ledi-Geraru. It was unmistakably Homo, the oldest confirmed fossil of our lineage.

When published in Science in March 2015, the finding pushed back human origins by 400,000 years. The 2013 excavation yielded more teeth awaiting analysis. A patient study would yield bigger surprises.

The Hidden Teeth

Between 2015 and 2020, researchers recovered 13 fossilized teeth from Ledi-Geraru, which were dated to be 2.6 to 2.8 million years old.

Some belonged to early Homo. Others belonged to a previously unknown Australopithecus species—one scientists thought vanished a million years earlier.

Two distinct human-like species lived in the same landscape simultaneously. Published in Nature on August 13, 2025, this discovery overturned assumptions about human evolution. We were not alone.

A Species Returns from Extinction

Lucy—a 3.2-million-year-old Australopithecus discovered in 1974—seemed to mark an evolutionary dead-end. Most Australopithecus species became extinct around 2.9 to 3 million years ago in the Afar region.

New teeth at Ledi-Geraru, dated to 2.63 million years ago, suggest otherwise. This species survived for hundreds of thousands of years longer than previously believed, persisting in the same region where early Homo sapiens emerged.

The fossil record hides far more than we know.

What the Teeth Can Tell

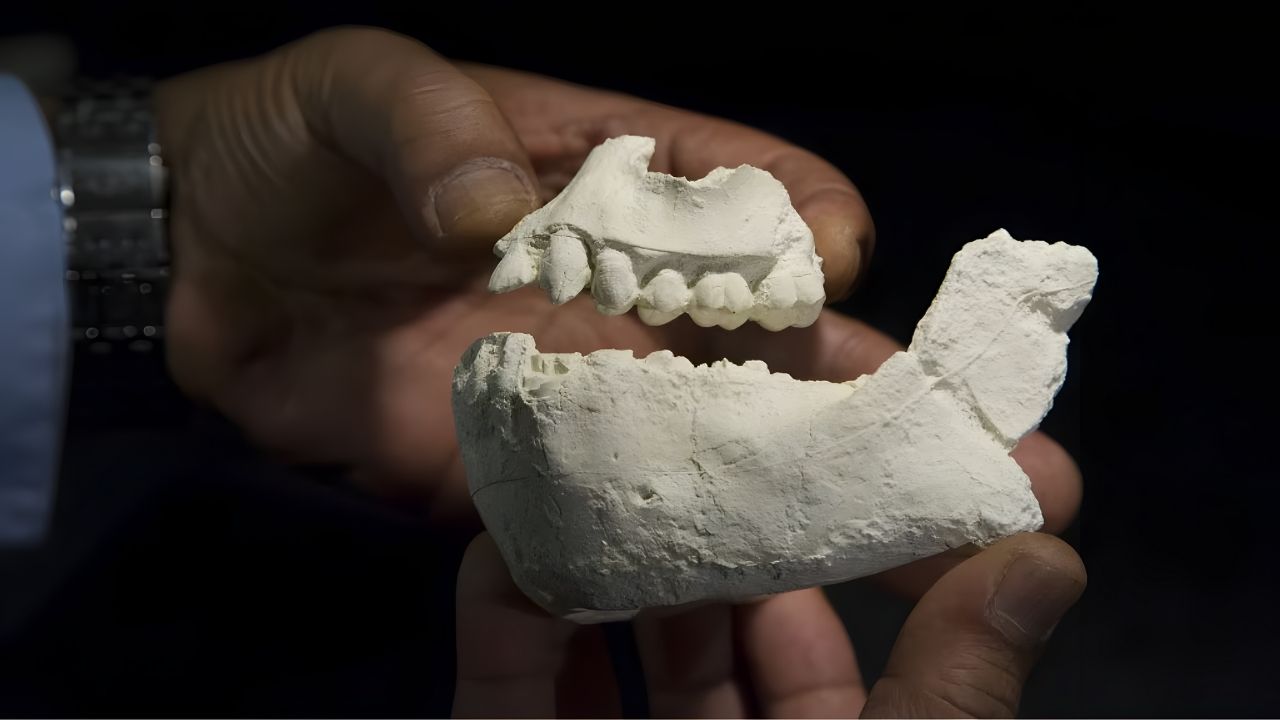

Fragmented fossils make teeth invaluable. Enamel preserves them for millions of years. Shapes, sizes, and wear patterns reveal species, diet, and behavior. Researchers morphologically compared the 13 Ledi-Geraru teeth against known Homo and Australopithecus specimens.

Argon-argon dating of volcanic ash pinpointed their age precisely. Dental microwear analysis revealed what these hominins ate and how they used their jaws. Teeth unlocked evolutionary secrets.

The Omo-Turkana Connection

A few hundred miles away in Kenya lies the Omo-Turkana Basin, spanning 4.2 to 1.5 million years of hominin history.

A 2025 analysis of 1,231 fossils by François Marchal at Aix-Marseille University reveals that early Homo and Paranthropus coexisted for 1.5 million years. Isolated teeth comprised 56 percent of all specimens.

The Ledi-Geraru teeth confirm the same pattern: multiple species shared landscapes, competed for resources, and adapted together.

Environmental Pressure and Adaptation

Between 2.8 and 2.6 million years ago, Afar wasn’t a barren desert. Geological analysis reveals a rapidly transforming landscape. The climate grew drier; grasslands expanded; forests shrank; and water sources became localized.

Evolutionary pressures intensified. Species adapting to new diets and behaviors survived. Dental microwear shows that both Homo and the new Australopithecus species responded to these pressures.

Did these species compete directly or partition the landscape into different niches? Further discoveries may answer this.

Why Teeth Matter More Than Skulls

Scientists dream of complete skeletons, but isolated teeth prove more informative about evolutionary relationships than partial skulls. Teeth resist decay, maintain consistent morphology through evolution, and clarify species links.

The Omo-Turkana record shows isolated teeth comprise over half of all hominin fossils. Ledi-Geraru’s 13 teeth answered questions that dozens of skulls might not.

Combined with radiometric dating, teeth anchor evolutionary history to absolute timelines.

The Search for the Missing Body

A key gap exists: Ledi-Geraru yielded teeth but no skulls, leg bones, or tool evidence. Homo teeth date 2.8 million years ago; stone tools appear roughly 2.6 million years ago—a 200,000-year gap.

Did Homo invent tools later, driven by competition or environmental stress? Were early tools made but not preserved? These questions drive next-phase research.

The team continues excavating, hoping to find skull fragments or limb bones revealing brain size and locomotion.

Coexistence Without Clarity

How did two human-like species survive in the same place without one eliminating the other? In the Omo-Turkana Basin, ecological partitioning provides answers. Early Homo ate flexible diets; Paranthropus specialized in tough, grass-based foods. Different resources meant less competition.

At Ledi-Geraru, we are unsure if this mechanism applies. Did Homo and Australopithecus avoid each other or compete fiercely? Isotope analysis of tooth enamel may reveal diet patterns and ecological separation.

The Question of Competition

Evolutionary biology teaches that two species cannot indefinitely occupy the same niche; one outcompetes the other. Yet at Ledi-Geraru between 2.6 and 2.8 million years ago, Homo and Australopithecus coexisted for hundreds of thousands of years.

This puzzles researchers. Either the species didn’t compete for identical resources, environmental conditions allowed both to persist, or competition occurred slowly. Eventually, Australopithecus vanished.

Homo survived and spread globally. Yet neither outcome was inevitable then.

The Bushy Family Tree

The old view of human evolution as a ladder climbing toward humans is dead. The Ledi-Geraru discovery confirms paleoanthropologists’ new view: human evolution was a bushy tree.

Multiple branches sprouted, some thriving, others withering. Homo coexisted with Australopithecus at Ledi-Geraru and Paranthropus elsewhere. Later human species overlapped for thousands of years.

Today, only Homo sapiens remains. We are not evolution’s inevitable triumph; we are one lucky twig that survived.

The Unfinished Story

Ledi-Geraru discoveries raise more questions than answers. What did early Homo eat? How large were their brains? Did they make tools or hunt? How did they interact with Australopithecus? Were other species present?

The fossil record remains fragmentary, with only teeth surviving. Yet, questions grounded in coexistence evidence, rather than replacement assumptions, represent major shifts. Continued excavation yields surprises.

The Ledi-Geraru Project’s work since 2002 demonstrates the power of systematic, long-term fieldwork.

Future Excavations and Emerging Methods

Ledi-Geraru continues systematic excavation, seeking cranial bone, skeletons, and stone tools, answering questions about early Homo’s appearance and behavior. Emerging technologies amplify fossil power.

Three-dimensional imaging reconstructs tooth shapes with unprecedented detail. CT scanning reveals internal structures invisible to the naked eye. Ancient DNA analysis, although challenging for old specimens, has yielded results in other hominin discoveries.

Isotope analysis reveals a diet with precision that is impossible to achieve through morphology alone. The next breakthroughs may emerge from studying existing specimens using new technology.

Implications Beyond Paleoanthropology

The Ledi-Geraru discovery resonates beyond academic paleontology. It fundamentally challenges our understanding of evolutionary processes, adaptation, and the dynamics of competition.

In ecology and conservation biology, findings showing early human-like species coexisting for hundreds of thousands of years without mutual exclusion inform modern species management. The Nature paper’s 20+ scientists from North America, Africa, and Europe demonstrate integrated, international approaches.

Funding agencies now recognize that major discoveries require sustained investment over decades. This model has a significant influence on future research support globally.

Addressing Misunderstandings

The discovery generated excitement, sometimes exceeding accurate understanding. Some accounts claimed Homo and Australopithecus “interbred” or competed in specific ways.

Scientists caution that evidence doesn’t support these claims. The fossils indicate coexistence, not interaction; overlap in space and time, rather than necessarily in ecological niches. Lucas Delezene, University of Arkansas, emphasized nuance: “Homo didn’t immediately replace all other species.

It lived alongside many throughout Africa.” Scientists study tooth isotopes and microwear to move from broad conclusions to specific answers.

When Assumptions Shift

Ledi-Geraru isn’t paleoanthropology’s first paradigm shift. Lucy’s 1974 discovery showed bipedalism preceded brain expansion, contradicting earlier assumptions.

DNA confirmed Homo neanderthalensis and Homo denisovans as distinct species, thereby overturning the single-species model. In 2025, Christopher Bae and colleagues proposed Homo juluensis from Chinese fossils, again expanding known hominin diversity.

Each discovery follows a pattern: surprise, careful reanalysis, refined understanding, integration into complex evolutionary models. Ledi-Geraru teeth exemplify this trajectory, demonstrating the capacity of evolutionary theory to accommodate new evidence.

The Bottom Line

The 2.8-million-year-old Homo teeth and previously unknown Australopithecus species discovered at Ledi-Geraru fundamentally reshape our understanding of human origins.

We are not evolution’s inevitable product; we are one branch on a bushy family tree. For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors shared their world with other human-like species. We competed, adapted, survived—by accident. Early human evolution wasn’t linear or guaranteed.

Climate, competition, and contingency shaped our path. Brian Villmoare notes: “Nature experimented with different ways to be human.” We were the experiment that worked.

Sources:

- UNLV News, November 24, 2025

- Nature, August 13, 2025

- CNN, January 24, 2025

- University of Arkansas News, August 12, 2025

- Fana MC, August 12, 2025

- Scientific American, August 13, 2025