On October 12, 2025, storm waters flooded Kipnuk, trapping residents in floating homes. They signaled for help with phone flashlights, a haunting image of helplessness.

Hurricane-force winds over 100 mph hit western Alaska villages as Typhoon Halong’s remnants caused severe destruction in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta.

Breaking Records

Storm surge levels broke records in several villages. In Kipnuk, water rose 6.6 feet above normal high tide, nearly two feet higher than the 2000 record.

Kwigillingok saw water reach 6.3 feet above normal tide lines, over three feet higher than its 1990 record. The National Weather Service confirmed these are the highest levels ever recorded in these communities.

Fragile Foundations

Remote Indigenous communities have faced increasing climate threats for years. Villages like Kipnuk and Kwigillingok, situated on permafrost along the Bering Sea coast, have experienced increased erosion due to the melting of sea ice and rising temperatures.

Since 1970, Alaska has warmed by 4.2°F, much higher than the global average of 1.7°F, making it one of the fastest-warming areas in the U.S. and changing settlement patterns that have been in place for centuries.

Sea Ice Loss

The disappearance of sea ice has removed natural barriers that protect coastlines. Now, the Bering Sea faces ice-free conditions during fall storms, which can bring typhoons to Alaska waters.

A 2024 study found that as protective ice has disappeared, wave heights have increased, and coastal flooding has become more frequent. This weakness, along with thawing permafrost foundations, has left communities unprotected against Halong’s unprecedented surge.

The Storm Hits

On October 12, 2025, the remnants of Typhoon Halong made landfall in western Alaska. Alaska State Troopers confirmed that 67-year-old Ella Mae Kashatok was found dead in Kwigillingok.

Two men, Vernon Pavil, 71, and Chester Kashatok, 41, are missing after their house was washed away. At least 51 people and two dogs were rescued from the floodwaters.

Communities Obliterated

Approximately 20 homes were washed away or destroyed in Kipnuk, and every building in Kwigillingok sustained damage. More than 1,500 people were forced to leave their homes in the area, making entire villages unlivable.

U.S. Coast Guard Captain Christopher Culpepper described the situation as “absolute devastation” during emergency briefings.

Helpless Witnesses

“Some houses would blink their phone lights at us like they were asking for help but we couldn’t even do anything,” recalled Brea Paul, a tribal court administrator in Kwigillingok who witnessed the Kashatok family’s house floating away.

Paul described the missing family members as “the most kindest people I’ve ever met” who “always had a positive mindset and they always greeted anyone—they welcomed everyone to their home”.

Shelter Crisis

In Kwigillingok, approximately 400 people sought shelter in the local school, which lacked functioning toilets and proper sanitation. The entire community gathered at schools around the area.

Residents reported power outages, no running water, spoiled food from freezer failures, and broken heating stoves. This damage puts winter survival at risk for remote communities that rely on stored food from hunting and fishing.

Subsistence Threatened

Alaska Native communities rely on subsistence foods for up to 50% of their daily energy needs. Rural residents collect an average of 295 pounds of wild food per person each year.

Climate change has disrupted the migration of bowhead whales, walruses, and caribou. Recently, a typhoon damaged freezers and food storage, making it harder for communities as winter began, when they depend on stored food.

Grant Terminated

In May 2025, the Environmental Protection Agency under the Trump administration canceled a $20 million flood protection grant intended for Kipnuk. The grant, issued at the end of the Biden administration, would have funded riverbank stabilization and flood protection for 1,400 feet of riverbank.

EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin revoked the grant, stating it was “no longer consistent” with the agency’s priorities, just months before the catastrophic flooding destroyed the village.

Community Frustration

The Public Rights Project, representing Kipnuk, confirmed that limited work had begun before termination, including the purchase of a bulldozer and hiring a bookkeeper.

Village leaders expressed frustration that federal support had evaporated precisely when their vulnerability to climate disasters had become undeniable. The timing of the grant cancellation and subsequent disaster highlighted the devastating consequences of withdrawal from climate adaptation funding.

Historic Airlift

Governor Mike Dunleavy issued a disaster declaration on October 9, activating Alaska National Guard and State Defense Force resources.

By October 15, the state conducted what Major General Torrence Saxe called potentially “the largest off-the-road-system response for the National Guard in about 45 years,” transporting approximately 300 evacuees to Anchorage aboard a C-17 Globemaster III aircraft. The Alaska Air National Guard’s 176th Wing transported more than 21,000 pounds of supplies to Bethel.

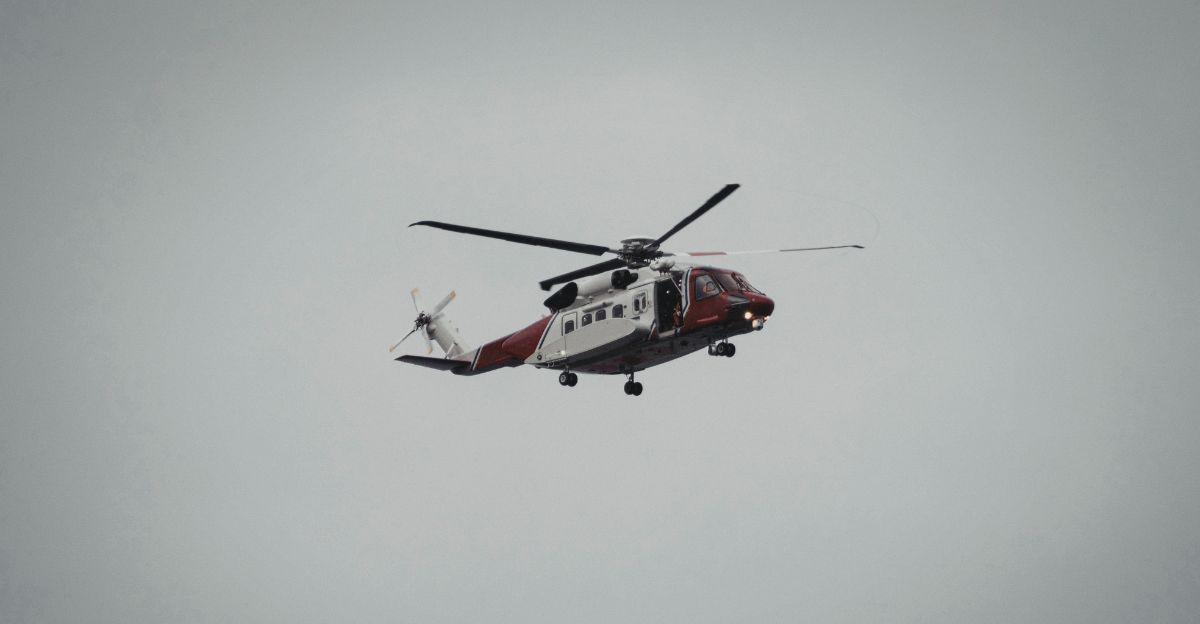

Search Suspended

Coast Guard and military teams searched dozens of square miles using helicopters, planes, drones, and boats before suspending active search operations Monday evening. “Suspending an active search is always a tough decision to make, and it is especially difficult in this situation where the Kwigillingok community is already suffering so much,” said Coast Guard Captain Christopher Culpepper.

Village public safety officers and volunteers continued local search efforts using drag bars and sonar equipment.

Recovery Challenges

Emergency responders shifted focus from search-and-rescue to stabilizing basic services and conducting damage assessments. The Alaska Department of Transportation reported more than 50 community airports and roads damaged by the storm.

Many Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta villages aren’t connected by continuous road systems, making local airports the only connection to outside communities—infrastructure now severely compromised.

Uncertain Future

As winter approaches within weeks, displaced residents face an existential question: whether their centuries-old villages can or should be rebuilt.

Climate projections indicate that permafrost is thawing at increasingly rapid rates, with coastal erosion erasing up to 100 feet of shoreline annually in some Alaska villages. With 144 Alaska Native communities now threatened by erosion, flooding, and permafrost degradation, funding for recovery remains uncertain.

Federal Response

The Trump administration’s approach to disaster management has drawn scrutiny following the Alaska catastrophe. Administration proposals include limiting disaster declarations to events with per capita impacts four times the current threshold, eliminating presidential declarations for snowstorms, and capping public assistance federal costs at 75 percent.

FEMA employees warned in an August 2025 letter to Congress that these changes could undermine disaster response capabilities developed in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

International Parallels

The disaster underscores global challenges of climate-induced displacement. No organized institutional framework exists for “climigration”—forced migration due to climate change. Federal agencies have documented Alaska’s erosion crisis since 2003, but failed to establish comprehensive relocation governance.

The EPA’s cancellation of a $20 million grant exemplified this policy vacuum, leaving vulnerable communities without adaptation support just months before catastrophe struck.

Cultural Survival

The disaster threatens languages spoken nowhere else on Earth. Yup’ik and Cup’ik, spoken in affected villages, have fewer than 10,000 speakers combined. Traditional knowledge systems—including ice safety assessments, seasonal hunting calendars, and fish preservation techniques—require specific landscapes for their practice.

Urban migration has historically disrupted language transmission among Alaska Native communities, with multiple studies documenting accelerated language loss when families relocate from traditional villages to urban centers, such as Anchorage.

Generational Trauma

The forced relocation echoes painful historical precedent. During World War II, 881 Unangax̂ (Aleut) people were evacuated from nine villages to abandoned canneries and mining camps in Southeast Alaska under harsh conditions. Seventy-four Aleuts died in the internment camps—32 at Funter Bay, 17 at Killisnoo, 20 at Ward Lake, and five at Burnett Inlet.

“Our ancestors said one day we will come upon this day,” said Agatha Napoleon, climate change coordinator for the Native Village of Paimiut. “I didn’t think it would happen in my lifetime”.

Defining Moment

Typhoon Halong marks the first typhoon remnants to catastrophically impact Arctic communities—a climate milestone scientists warned would arrive by mid-century. Federal disaster declarations for Alaska have increased 400% since 2000.

With 144 Alaska Native villages now threatened by erosion and flooding, the Kipnuk disaster tests whether policy can keep pace with the rapid changes in the Arctic. Congress is scheduled to review Alaska relocation funding requests in November 2025.